A 9/11 Origin Story

It’s staggering to think that the post 9/11 world is now old enough to drink. Twenty-one years after the day that changed the lives of everyone on Earth at the time, the United States is pivoting away from the counterterrorism focus unleashed by al-Qaeda’s attacks and targeting China and other nations that threaten the international order.

Afghanistan has reverted largely to status quo anti with the Taliban back in power and some degree of al-Qaeda presence. The significance of that presence is a topic of debate. The 20-year war did knock al-Qaeda down in Afghanistan, but never eliminated it. To date, the Taliban maintains close ties with al-Qaeda, and the fact that the head of al-Qaeda was killed by a U.S. strike while residing in a house in the heart of Kabul does not bode well. Terrorism hawks argue it’s a sign that al-Qaeda is rebuilding in Afghanistan and more 9/11s could be on the horizon.

Still, publicly available reporting on al-Qaeda in Afghanistan indicates the group maintains small numbers and limited capabilities. While it might have grand ambitions, it lacks the ability, for now, to carry out major operations like 9/11.

Unfortunately, more robust al-Qaeda cells in other locations—Yemen, Libya, and several countries in Africa—highlight how the problem has spread and metastasized in the years after 9/11.

And then, there’s ISIS, which evolved from al-Qaeda in Iraq, which did not exist until after the unnecessary and badly executed toppling of Saddam Hussein in 2003. That operation unleashed a wave of terrorism that culminated in tens of thousands of ISIS members seizing a large swath of northern Iraq and eastern Syria (the war also empowered and emboldened Iran in the region). Despite successful operations to retake the territory that ISIS controlled, there are still thousands of ISIS members in the region, not to mention offshoots/franchises in Afghanistan, Libya, the Sahel, Yemen, and the Philippines.

Bottom line, there are far more terrorists in the world today than on 9/11. Fortunately, most lack the ability and resources to plan and conduct attacks on the scale of 9/11, but they do have the desire, intent, and ability to conduct or inspire attacks like in Paris in 2015, the Pulse nightclub, or San Bernardino.

Of course, the uncomfortable reality is that in the United States, mass shootings by individuals not tied to or motivated by groups like ISIS kill far more people each year than terrorists do. So, arguably counterterrorism operations and activities have been far more successful than efforts to eliminate gun crime in the country.

Hence, counterterrorism has receded in strategic importance as China has grown more powerful and assertive. However, terrorism is certainly an ongoing concern as evidenced by ongoing U.S. CT operations in Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and possibly elsewhere.

Those operations in one way or another were at the center of my life as a journalist and government official since 9/11. As cliche as it might be, 9/11 altered the course of my professional and personal life. The following is from an early draft of my forthcoming book. The chapter details 9/11. I subsequently cut all but a couple of key paragraphs that explain how that day started my journey to become a war correspondent.

September 11, 2001, started as a typical Tuesday morning at WBUR in Boston. The other producers of the NPR program The Connection and I were at our desks in our brightly lit corral. Surrounded by piles of books and newspapers, we were deep into the pre-production process for our daily programs. From 10 a.m. until noon we would be live discussing a different topic each hour, and several hundred NPR stations across the country would be airing the programs.

On the other side of the divider, the staff for Here and Now was immersed in pre-production for their noon show. The air was filled with chatter as producers and hosts discussed scripts and rundowns while other producers spoke with prospective guests by phone. It was a slow news day, and the energy was as relaxed as a busy newsroom gets. Our first hour was a discussion about nanotechnology and the second hour a conversation with Stefan Fatsis about his book Word Freak. Again, it was a slow news day.

I had joined The Connection a few months prior, and it was my first gig in the news business. I hadn’t planned on becoming a journalist. If you had asked me in college what I thought my possible careers were, journalism would not have crossed my mind.

From 1994 to 2001, I worked in the Boston area as a recording engineer and producer and occasional guitar player. I wrote for some music publications as a side gig because I enjoyed writing, but never thought of it as a full-time thing.

However, my music career had been plateauing. I had worked on some successful projects and had engineered a few blues albums that people in the Boston blues scene dug. Unfortunately, I became a victim of that success. While I dreamt of working with artists like Los Lobos or Richard Thompson, I was stuck cranking out blues recordings that recreated the sound of 1950s records.

During one such session, I hit the wall. While listening to the playback of a sloppy take of an uninspired song, I felt the need to slit my wrists. I realized I had to get out to stay sane. I dumped that project on another engineer and started job hunting.

I came across a job posting for a technical director at WBUR. It was essentially an audio engineering position for a live radio program. I applied and didn’t get the gig because I had no live radio experience. However, the station brought me on as a freelance engineer to get experience and in the spring of 2001, they hired me as a full-time technical director for The Connection.

I was quickly pushed into producing programs—researching and pitching ideas, booking guests, preparing briefs for the host, and writing program intros—as well as doing audio production work. I was immediately far more interested in the substance of the programs than the technical process. Intellectual receptors in my brain lit back up after years of being dimmed by the late nights in recording studios.

On the morning of 9/11 I was a little more tense than usual as the primary engineer for the show was on vacation and I would be operating the board. While I had years of experience as a recording engineer manning studio consoles, I had only a couple of hours of live radio board operation under my belt, and I was still getting comfortable with it.

A little before 9 a.m., a newsflash came across the wires that a plane had crashed into one of the Twin Towers. I immediately assumed it was something like the time in 1945 when a B-25 got lost in the fog and crashed into the Empire State Building. It was odd and tragic for those involved but wasn’t quite “holy shit” news.

A few minutes later I walked into the studio to start setting up for our program. I blithely mentioned to the three colleagues in the control room that a plane had just hit the World Trade Center. We remarked how odd that was and I noted the example of the Empire State Building as we casually chatted about it. Such was the jaded response of journalists to a deadly incident, at least at that time.

Then, the “holy shit” news came over the wires—another plane hit the second tower. At that point, we all knew it was no accident, and most likely a terrorist attack.

We went into full-on breaking news scramble. We canceled our two scheduled programs and called all the Boston-based national security and counterterrorism experts in our Rolodexes. Yes, in 2001 many of us were still using analog technology like Rolodexes. For the millennials reading this, ask Siri or Alexa what a Rolodex is.

We forged ahead mapping out breaking news coverage as managers at the station got on the horn with NPR in Washington to discuss the game plan. After some back and forth, NPR informed us that they were going to go live with special coverage out of Washington that would preempt our show and we could stand down. They advised us to put on CD of a past show so there was still programming on the wire as a backup. I dug up a disc and had it ready to play.

We all throttled back and started focusing on how we should proceed in the coming days. At 9:55 a.m., we received a call from NPR saying they were not able to pull it together to go live, and they needed us to go on and provide national breaking coverage.

I sprinted into the control room to prepare. I was already nervous about running the live show, let alone during the biggest news story of our lives.

Typically, the one-minute “billboard” at the top of the hour summarizing the program was pre-recorded, but there was no time for that. Just like Bill O’Reilly on Inside Edition, we had to fucking do it live!

At 10 a.m. on the dot, I opened the host microphone and the director pointed to Michael Goldfarb to start reading. There was dead silence. I felt a rush of panic like never in my life. I looked at Michael and he was reading, but there was nothing. It was like punching the hyperdrive on the Millennium Falcon and hearing that sad sound of faltering engines.

My heart was in my throat. I frantically looked over the board, and nine seconds after the top of the hour I saw that the output assignment for the microphone was not engaged. I hit the button and again pointed to Michael. He started reading. Because of the late start, we were not going to hit our post at 10:00:59. I had to cut off his mic mid-sentence to hit the post. It was a shitty way to start the program—10 seconds of dead air and then chopping off the host in mid-sentence. It was live radio. In hindsight, it was an authentic representation of the chaos and holy shitness of the moment, but at the time I felt like Danny Noonan leaving the putt at the lip of the cup.

I had a few minutes during the newscast to catch my breath and figure out what the fuck had gone wrong. The rule was that when you finished in the control room, you “normalized” the board so it was ready to go for the next person. Part of that process was setting the mic assignments to the primary output.

For whatever reason, the last person to use the board had not done that, and none of the microphones had been assigned to any output. On any other day, I would have caught that in pre-production, but since we had to jump in on short notice, and I was still green, I didn’t have time or presence of mind to check before we went live. It didn’t help that the TV in the control room showed the South Tower collapse at 9:59, which added more stress and chaos to the moments before we went on air.

I made sure the board was ready to go when we went live after the newscast. Things progressed without incident—as in any additional technical errors on my part. At one point I looked up at the TV just as the North Tower collapsed. I couldn’t let myself process or react to it as I had to keep my fingers on the faders and bring guests and callers in and out.

Thousands of people were dead or dying in a world-changing act of terrorism, and we had to button up any human response and focus on the task at hand. I had never experienced anything like that before. I certainly had no training or preparation for anything like that.

When we got off air just before noon, I was shaking from the stress and adrenaline. That afternoon, we held our usual editorial planning meeting. It was somber but focused. The work was what mattered. We had to focus on how to best inform and serve the audience. The stakes were high, and we had to deliver. I had to continue driving the show the rest of the week, and that just added to the stress for me. After we got off air on Thursday the 13th, I was so anxious that I felt ill. I had to go lie down in the green room for 20 minutes to calm down and let all the stress chemicals flooding my system fade.

For the next few weeks, we were so focused on the story, on booking guests, on planning shows, that I really didn’t have a moment to step back and process it all. Breaking news coverage is like ER surgery—turn off your emotions and do the job.

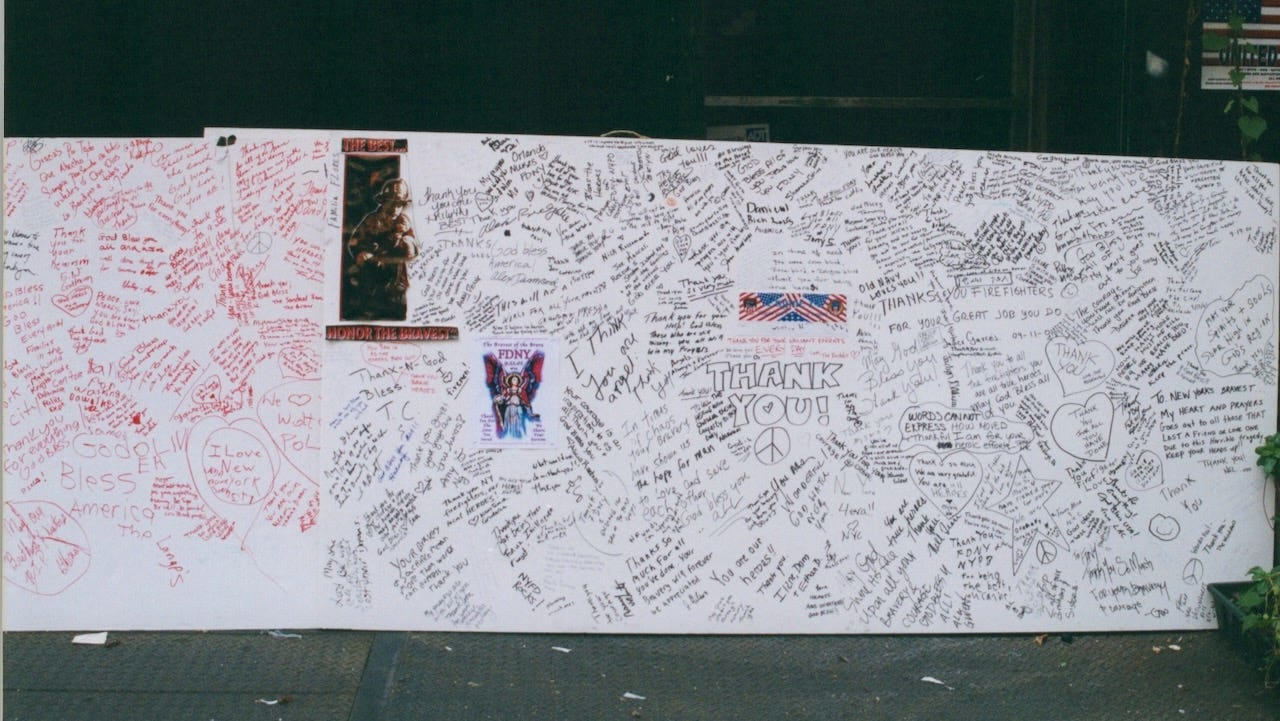

In early October, I decided to visit New York City for a weekend to see the aftermath and give myself a chance to process it as a person. Unfortunately, I failed. As I approached Ground Zero, I saw others looking to do the same thing—see it and process it. My journalist brain kicked in and I ended up interviewing everyone else about why they were there and what they thought and felt. It was my first time experiencing what would become the norm in my career: witness horrible things or the aftermath of horrible things, talk to people about their pain and suffering, and stuff away my feelings or reactions and tell their stories.

By the time the invasion of Afghanistan was under way, the production rhythm had stabilized. I often spent mornings dialing satellite phone numbers trying to reach people on the ground in Afghanistan to get them on the program. I was typically calling one of the Karzais or one of the handful of rock star foreign correspondents covering the special forces and Afghans driving out the Taliban.

That lit the fire in me. Talking to Dexter Filkins, Sarah Chayes, or Anthony Shadid over spotty connections as they vividly described the Afghan landscape, the fighting, the history in the making: I was envious. Yes, I was doing my part as a young—in my career at least—journalist to help inform the American public what was taking place over there. However, I couldn’t help but feel that sitting in a studio and talking to the people in the field who were risking their lives to tell incredible stories was not where I wanted to be.